Three Months in New York: The Development of Bro. Muhammad Juma’a

Author’s Note: There is no correct or standardized response to the question, “What does Masonry do?” Every member joins for a different reason and every member’s journey tends to lead them down a different path over time. If, as in a Venn diagram, you had to find commonalities in the responses, you would be likely to find the largest overlap around the idea of self-improvement. The ideas of diversity and of self-improvement are what this Article is written about seen through the window of a few months in the life of Bro. Muhammad Juma’a of Oman (1815-1840) while he was in New York City.

Much like the previous Article (Article No. 2, “Power of the Press”), I hesitated about publishing this because Juma’a became a member of a Lodge in which I am a member, St. John’s Lodge No. 1. My preference as the Master of The American Lodge of Research this year is not to show favoritism or bias in my writing, however, Juma’a’s experience with the Lodge is limited to just one small section. The core of this interesting story has more to do with his personal growth and desire for improvement as a result of Masonry; attributes that could be found had he joined any Lodge in the city at the time.

There is something about Juma’a and his time in New York that resonates with me. When I think about the striking image of Juma’a and his compatriots being escorted across the East River while they stood at the head of their respective boats, green robes flowing behind them, I have to wonder what would be going through the heads of the many observers lined along the river. It would probably be one of awe and curiosity. I am also curious about what Bro. Juma’a would have thought as he sailed across the river that day. His excitement and his wonder at his observations of the city would have likely been tempered by his levelheaded demeanor and the methodical way in which he approached his responsibilities. His experiences in the city and with Masonry during this brief period in his life are described in detail here.

Signature of Bro. Muhammad Juma'a in the St. John's Lodge 1784 Bye Laws Book

The Sultanate of Oman is a country on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula located near the mouth of the Persian Gulf. At the time of our story, however, it was known as the Sultanate of Oman and Muscat and its territory stretched south to the island of Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, and as far west as Gwadar in present day Pakistan. The Sultanate was ruled, then as now, by the Al Busaid family, also known as the House of Al Said. The absolute monarchy took power in 1749, after Ahmed bin Sa'id Albusaidi expelled the Persians from Oman and established Muscat as his capital. The country became a dominant player in global trade, with many Omani merchant princes establishing trading relationships throughout the region.

In 1807, Said bin Sultan Al-Busaidi came to power and ruled until 1856. This was a time of great prosperity for the Sultanate. The Swahili people along the coast of East Africa invited his expansion to the island of Zanzibar and, as a result, Al-Busaidi alternated his capital from Muscat, in Oman proper, to Stone Town on the island in 1840. The distance between the two cities of almost 4,000 kilometers showed the strategic importance that Al-Busaidi placed on this trade depot in the Indian Ocean.

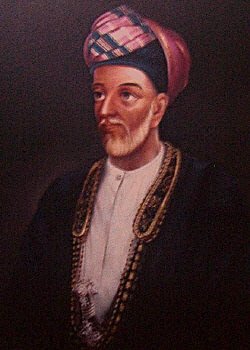

Said Bin Sultan of Muscat, Oman and Zanzibar

A bit prior to this time, the forward-thinking Al-Busaidi began a series of negotiations with the United States Special Agent to Oman with a goal of constructing a treaty that would establish mutual recognition of the two countries. These negotiations represented some of America's first official dealings with the Middle East. A treaty was ultimately established in 1833 when Roberts arrived with a letter from President Andrew Jackson which provided very favorable terms for Oman. A strategic alliance made sense for the Americans. Al-Busaidi, whom the Americans referred to as “the Imam,” had proven to be a reliable ally and exceptional friend in the hostile waters of the Indian Ocean. Beginning as early as the George Washington administration, American sailors cruised into Oman’s harbors to trade their cotton and tobacco products for aloe, gum Arabic, Mokha coffee and Omani dates.

While the Sultan had observed and greeted the sailors and merchants frequently arriving from America, he began to wonder about the possibility of sending an Omani ship directly to the American shores on a trip that would be commercially oriented while at the same time designed as a gesture of goodwill towards the country. On December 23, 1840, Al-Sultana, a merchant ship constructed of teak, set sail from Muscat towards New York City with stops at Zanzibar and St. Helena. Onboard the ship was the Sultan’s envoy, Ahmad bin Na’aman, an Arab born in Basra, who would become the first diplomat from Oman accredited to the United States. The ship was loaded with letters and gifts for the President of the United States, Martin Van Buren, as well as with two Arabian stud horses, Omani dates, Persian wool carpets, over one-hundred East African ivory tusks, Mokha coffee from Muscat and various articles from Zanzibar. The Sultana sailed under the command of an English sea captain, an Arab emissary, African and Persian officers, and a crew composed of South Asian and East African sailors. Also onboard that ship, the first one from Oman to touch the shores of America, was Ahmad bin Na’aman’s right hand man, a twenty-five year old sailor, First Lieutenant Muhammad Juma’a.

Dr. Kamari. Omani Ship Sultana Under Full Sail.

Juma'a was Swahili by birth; meaning he spoke the Swahili language and was from the East Coast of Africa at Zanzibar. Although he was second in command to his superior, First Lieutenant Muhammad Abdallah, he was the de facto senior sailor onboard the ship. He was described by his contemporaries as "a big black nosed chap" of mixed Afro-Arab descent. He had a deeply pockmarked face and was cheerful and liked by all. Most importantly, all aboard recognized that he had considerable intelligence and a keen desire to broaden his previously limited horizons.

The Sultana arrived in New York harbor on April 30, 1840 after an eighty-seven-day voyage under the red flag of the Sultanate and docked along the burgeoning and bustling seaport on Manhattan’s eastern shore. The ship was in poor shape upon its arrival, which along with his significant drinking problem while onboard, led to the dismissal of the English captain William Sleemen. The city of a little over 300,000 inhabitants was fascinated by the entrance of the ship and excited by the sight of the fifty-six sailors onboard. The entire crew were widely entertained while in New York and the Omani envoy bin Na'aman was given the "civilities and accustomed hospitality of the city" by New York City officials. It was at this time that Na’aman’s portrait was painted by the artist Edward Ludlow Mooney. The 42 by 36-inch painting was displayed in the offices of the Art Commission of New York City, while a copy was given to Na’aman in gratitude for sitting for the portrait (currently in possession of the Peabody Museum of Salem). The portrait shows Na’aman in an elegant gold coat and silk turban staring straight at the artist.

Mooney, Edward. Portrait of Ahmad bin Na’aman, 1840. Peabody Essex Museum.

While the crew began to offload their cargo to New York City merchants in exchange for a return cargo of textiles, gunpowder and muskets, china plates, mirrors, gold thread, and sperm whale candles, they attracted considerable attention by the gathering crowds of citizens. Not content to simply observe the crew, many curious New York residents began to force their way onto the ship which almost led to the crew being overrun. From that point until their departure, the city placed two police officers onboard at all times to deter another attempt by the crowd.

The gifts that had been procured for President Van Buren could not be formally accepted by him, as it was stated that Congress felt it would be inappropriate to receive them. As a compromise, and to not insult Said bin Sultan Al-Busaidi, Congress agreed to accept them under the condition that they were instead accepted on behalf of the United States government. As a result, gifts of a gold-mounted sword, four Cashmere shawls, a Persian carpet, two Arabian horses and saddles, a case of attar of roses, and a box of pearls were deposited at the National Institute Gallery in the Patent Office.

Van Buren Pearls. Gift of Imam of Muscat in 1840. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Having successfully offloaded their cargo, the officers, including Juma’a, were given tours of New York City and its cultural institutions. The officers wore their traditional clothing, which gathered even more attention by the crowds. The New York Common Council, on May 13th, gave them a tour of the Institution for the Blind, had lunch at a home in Morningside Heights, took a short ride on the Harlem Railroad, which was a first for the officers, a visit to Blackwell’s Island, Bellevue and finally to a dinner in their honor at City Hall.

The Secretary of the Navy, James K. Paulding, gave instructions to the Commodore of the Navy Yard in Brooklyn, James Renshaw, that he should “pay every attention to the Commander and officers of the vessel lately arrived.” Recognizing that the Sultana was in need of significant repair work after its long journey across the Atlantic and fulfilling the wishes of Paulding, Commodore Renshaw requested that the officers join him at his home on May 18th. At eleven in the morning that day, four trim navy boats were sent across the East River towards Castle Garden to pick up each of the crew members. Juma'a and the other officers were wearing "long robes of deep green color, buttoned up the front," with Juma'a wearing Lynn shoes that had been procured in Zanzibar, although they had originally been acquired in Salem, Massachusetts. When the four boats entered the water, the United States ship North Carolina fired off a thirteen-gun salute to welcome them aboard. While Envoy Na'aman and First Lieutenant Abdallah were excited, Juma’a proved to be shier in his interaction with the United States officers aboard the North Carolina and those at the Navy Yard. Afterwards, the Omani officers went on to dine with Commodore Renshaw, although Juma’a spoke little English during the meal. Throughout the day, the officers would retire briefly in private for prayers towards Mecca in the mid-afternoon and at sunset and spent the night at the Commodore's home.

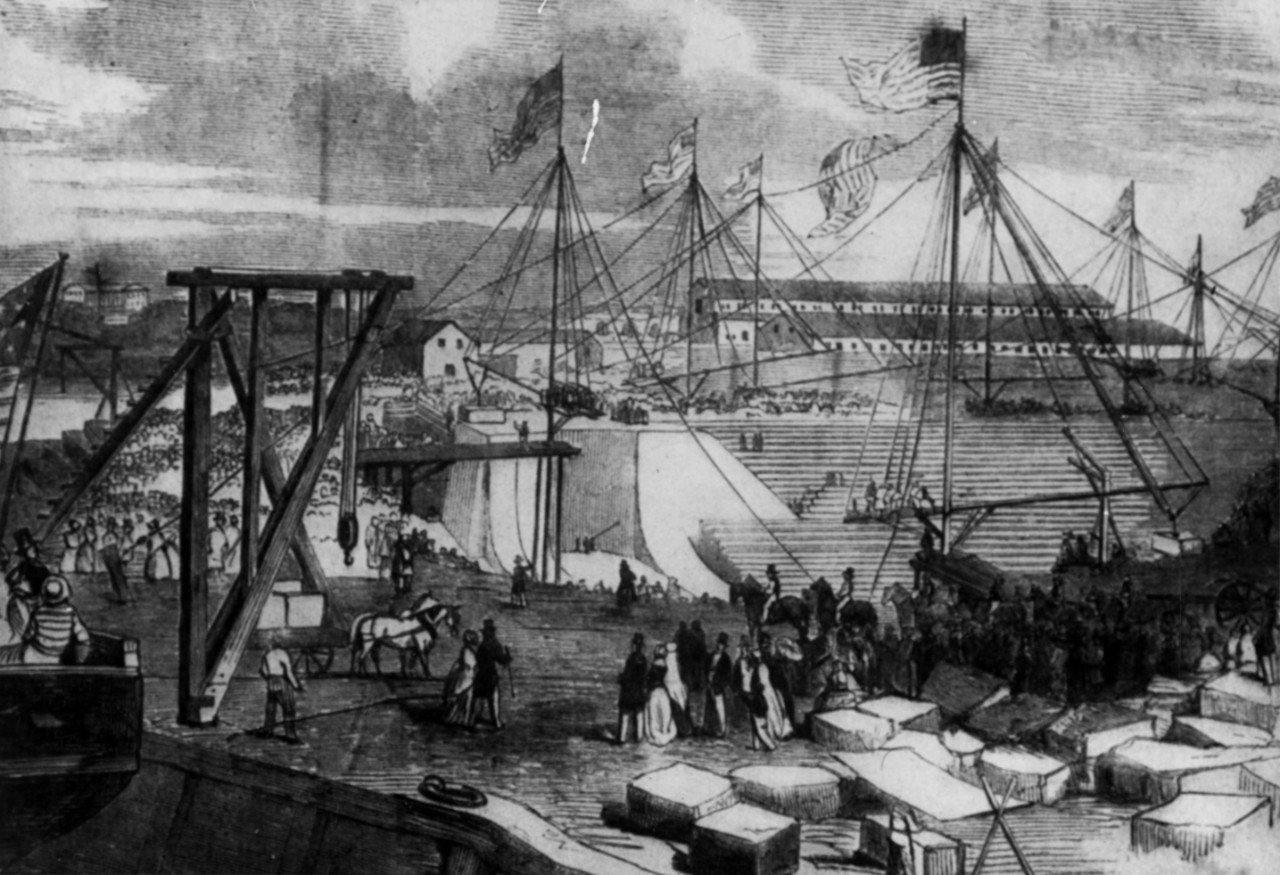

New York Navy Yard. Depicting the construction of the yards dry dock in 1849.

A few days later, on the 23rd, the officers of the Sultana, along with the Mayor of New York City, were invited by the president of the Long Island Rail Road to take a trip on a special car to the line's easternmost terminal at Hicksville, New York. Juma'a and the other officers arrived at the rail station at Clinton and Atlantic Streets in Brooklyn for the ride out. Along the twenty-seven-mile, two hour trip, huge crowds gathered to try and catch a glimpse of the visitors and the officers were shown how to operate the train in the huge locomotive. Upon arriving in Hicksville, they were taken to the Grand Central Hotel for a lavish feast.

Shortly thereafter, authority was granted to retrofit the Sultana at the United States government's expense and the ship was towed to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for two months of repair work. The officers were quartered with the Commodore throughout this time. While the log book of Ahmad bin Na'aman show advances for payments to the officers and crew as they took in the sights and experiences of New York, Muhammad Juma'a took the opportunity to expand his horizons. He frequently met with the wife of Commodore Renshaw at their home where she instructed him in English and provided him with a number of books. By the time he departed a few months later, Juma'a could read English fluently and write it fairly well.

The day after the Sultana was towed to Brooklyn, Juma’a was formally proposed to become a member of St. John's Lodge No. 1 by the Worshipful Master, Robert R. Boyd. On June 11th, at the meeting place of the Lodge at Howard House (also known as Howard Hotel) on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane, Muhammad Juma'a was brought forward and received the degree of an Entered Apprentice. It was impossible for the Lodge to procure a Quran for the evening with such short notice and when Juma'a was informed that he would need to take his obligation on a Bible, he asked whether the Bible contained a belief in a supreme being. The answer was affirmative and Juma'a remarked that it was a good enough Quran for him.

Two days later, on the 13th, Juma'a and the other officers were guests at the Commodore's gala reception for Governor William Seward. On the evening of the 16th, Bro. Juma'a was passed to the degree of Fellow Craft and raised to the degree of a Master Mason in due and ancient form. Juma'a attended at least one Lodge meeting as a member. His beautiful signature is recorded in script in the Lodge's Bye Laws Book from 1784 as a signer under the 1836 bye laws changes.

On July 10th, Juma'a and the ship's officers met with Vice President Richard M. Johnson at the Commodore's home. Plans were being made for the return voyage of the ship, however, the entire crew refused to sail under the previous English captain. Captain Sandwith Drinker of Philadelphia, who previously spent significant time in Macau, was instead brought aboard for the trip across the Atlantic in the newly retrofitted ship. On August 7th, the ship cleared customs, was towed past Sandy Hook, New Jersey and departed for home.

The ship encountered unseasonable weather and the officers and crew, with the exception of Juma'a, seemed to be lacking in their efforts. The first lieutenant was sick and barely left his bed and the crew were likely dispirited from their prior experience under the dismissed captain. Juma'a, however, proved his worth to Captain Drinker. Despite suffering from what was likely Guinea worm disease (dracunculiasis), which impeded his ability to walk and required constant poulticing, Juma'a and Drinker worked out a schedule to keep watch day and night throughout the journey. Drinker was aware of Juma'a strong desire for self-improvement and before leaving New York City purchased a copy of Nathaniel Bowditch’s American Practical Navigator for him. Drinker occupied himself by teaching Juma'a in the principles of navigation with this guide and with the instruments onboard. They took the measurements of the sun every day and Juma'a was able to quickly pick up on how to record longitude and latitude. This helped inform the entire crew which direction Mecca was located for their daily prayers. Captain Drinker recorded in his journal that Juma'a "is persevering and has a comprehensive mind... I am most pleased with him... in fact, he has the most amiable disposition I ever met with."

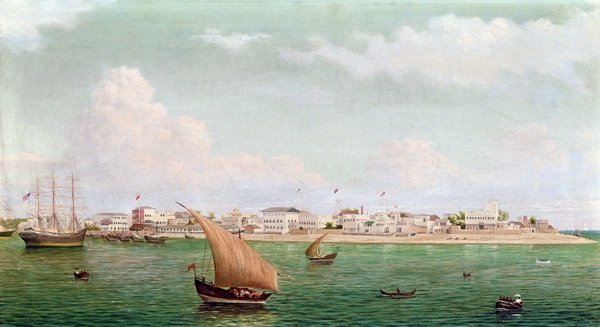

When the month of November arrived, the entire crew participated in the Muslim fasting of Ramadhan. The crew only touched food after sunset and made preparations for Id al-Fitr which would mark the celebration of the ending of fasting. Finally, on December 7th, the ship arrived at Chumba Island, just several miles from Zanzibar. Juma'a rowed ashore to return the following day with a pilot and vessel to help the ship navigate to anchor in Zanzibar.

Brown, Charles Porter. Zanzibar Harbor, 1878.

Muhammad Juma'a arrived the following morning with the news that the families of the sailors in Zanzibar were all doing well and looked forward to the return of the crew. The day would prove fateful, however, as shortly after arriving onboard Juma'a was recorded as having risen "from his chair and walked to the side of the ship, and stood looking over, suddenly he put his hand to his throat, as if choking, before anyone could reach him, he reeled overboard and sank immediately."

Juma'a's death was lamented by all of the crew and Drinker was deeply distressed at having lost his pillar of strength on his long journey across the Atlantic. It is uncertain what exactly happened to him in his final moments. St. John's Lodge must have been informed of his death, as next to his name it is recorded that he was dead and that he was "an officer in the service of the Imaan of Muscat."

While Captain Drinker was teaching Juma’a about navigation and how to captain a ship, Juma’a was teaching Drinker in a more subtle way. The observation of Juma’a’s character, as well as his constant desire for self-improvement, must have left an impression on Drinker. After Juma’a’s death, the captain began building a social circle of Freemasons who shared the same values as he established a mercantile career in Hong Kong. Sandwith Drinker would go on to become a Freemason and the Worshipful Master of Zetland Lodge in 1850-1851; Zetland Lodge being the second established Masonic Lodge in Hong Kong, in March, 1846.

The venture to New York City was a success for the Sultan and his deputy Na’aman. The commercial trade that was conducted fetched higher prices than would have been achieved by going through middlemen merchants in Zanzibar. The gifts sent back to the Sultan from the United States brought an aura of prestige to Oman, with the Sultan further sending additional gifts to President John Tyler in 1844. The Sultan’s gifts to President Van Buren were transferred first to the Treasury Department and then to the Smithsonian Museum, where some of them can be found to this day. The Sultana would carry gifts to Queen Victoria of England in 1842 and its fate would ultimately end with its wreck off Wasin Island while returning from a voyage to India.

WORKS CITED

Butt, Rudi. “Philadelphia Quaker, Soldier of Fortune: The Story of Sandwith Drinker.” Hong Kong’s First, July 24, 2014. http://hongkongsfirst.blogspot.com/2012/02/philadelphia-quaker-soldier-of-fortune.html

Eilts, Hermann Frederick. A Friendship Two Centuries Old: The United States and The Sultanate of Oman. Washington, D.C.: Sultan Qaboos Center, 1990.

Eilts, Hermann Frederick. “Ahmad Bin Na’Aman’s Mission to the United States in 1840, The Voyage of Al-Sultanah to New York City.” Essex Institute Historical Collections Volume XCVIII (October, 1962).

“Gifts From the Imaum of Muscat.” From the Archives. The Smithsonian Institution. December 21, 2021. https://www.si.edu/Content/Governance/pdf/Archives_06-24-2013.pdf

Macron, Mary Haddad. Arab Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland. Cleveland: Cleveland State University, 1981.

Prestholdt, Jeremy. “Sultana: The Odyssey of an Oman-Zanzibari Ship in Nineteenth Century America.” YouTube video, 42:59. January 24, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mRYyaG3dCUA.

“U.S. Relations With Oman.” U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State, Burea of Near Eastern Affairs, December 13, 2020. https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-oman/.